Harpers Bazaar

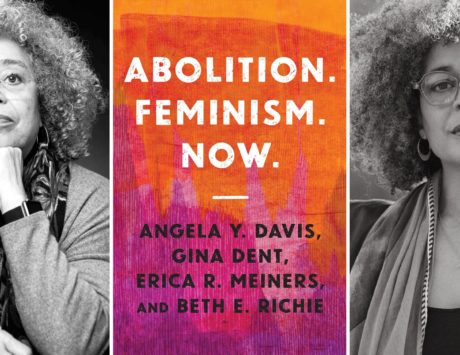

The activists detail how their latest book, Abolition. Feminism. Now. came to be.

In 2003 author, scholar, and world-renowned activist Dr. Angela Davis published Are Prisons Obsolete, a landmark book arguing that prisons, along with other carceral institutions, should be abolished. It’s a subject that Dr. Davis has been rigorously studying and organizing around for decades, especially during her own period of incarceration and then acquittal on murder and kidnapping charges in the ’70s. Now Dr. Davis, in collaboration with fellow scholar and writers Beth Richie, Erica Meiners, and Gina Dent, has revisited the subject of anti-prison activism in her latest book Abolition.Feminism.Now.

BAZAAR.com spoke with Dr. Davis and Dr. Dent about their new book, what justice without prisons looks like, the passing of bell hooks, and more.

Some people might think feminism and abolition are at odds with one another because so much of mainstream feminism’s response to violence against women is a carceral one. Can you explain what the two movements have to offer to one another?

Angela Davis: That’s precisely why we decided to write this book: because we wanted to encourage people to think about feminism and abolition together. Of course, neither movement is a unitary movement. We don’t identify with mainstream feminism. We don’t identify with carceral feminism. But there are also strains of abolitionism that we might not embrace. There are those who put undue emphasis on the process of destroying or abolishing or dismantling, and we point out that abolition is about rebuilding, reenvisioning, reimagining, reconceptualizing. So what we’re arguing is that the feminism we think is most effective is anti-racist feminism. Anti-capitalist feminism. [Those] are rendered much more powerful, much stronger, by embracing abolition, and abolitionist movements are much more effective when they embrace anti-racism, anti-capitalism feminism.

Gina Dent: What we’re really talking about is that any feminism that is really worthy of the name, that is really about the liberation of all, can’t be a feminism that’s attached to carceral policies. So that’s really the emphasis in the book, that in many ways the abolitionist strategies that we know about are actually feminist abolitionist strategies, but often the name feminism is not attached to them. We want to try and make it possible for people to see how necessary feminism has been to prison abolitionism, just like we want to be able to see how necessary it is for feminists to challenge themselves by thinking about abolition.

Many people understand that prisons and other carceral institutions are inherently oppressive and need to be done away with, but many of those same people struggle to imagine a future where victims of violence, particularly rape, murder, and assault are given any type of justice. For you, what does a post-abolition form of justice look like?

AD: I would begin by pointing out that responses to violence that focus myopically on the individual fail to recognize the larger social processes at work that produce and reproduce those violences, and are bound to be unsuccessful. So we criticize carceral feminism that assumes that one can deal with rape and other forms of gender violence simply by incarcerating the individual perpetrator and not taking into consideration the larger social context that produces violence against women.

In the book we constantly tried to point out abolition is about rebuilding even more than it is about dismantling. Ruthie Gilmore for example says that “abolition is less about prisons than it is about presence.” We think about the process of getting rid of prisons in conjunction with presenting new modes of justice. We cannot continue to have a retributive justice system if we want to imagine new ways of addressing the issues that prisons simply cannot address. Justice, in the form that we know it, is always designed to deal with one individual case, leaving all the structures intact that are responsible for the reproduction of that violence. But we see justice as transformative, as transforming not only individuals but transforming our societies. This is one of the major arguments of the book, that in the same way we have to learn how to think in structural terms about racism, we also have to think in structural terms about gender violence.

GD: Part of your question is interesting because it assumes that those violences like rape and murder will persist into the future and that we will need some system to address them. A part of what we’re talking about, and that abolitionist feminists have been talking about from the beginning, is really that the work we would do to end incarceration would also end those forms of violence. In other words, by attending to interpersonal violence and sexual violence simultaneously, the work of building a different and transformed society would also rid us of many of these other social ills.

You both are prominent figures in the modern-day abolition movement, who were the people you looked to when you were beginning?

AD: Prison intellectuals. The people in prison doing intellectual work are probably the most important but underlooked, under-examined, and misunderstood, founders of this movement. This is really a movement that comes out of jails and prisons and cells. I think about George Jackson’s analysis of the prison system back in the early 1970s and the role that incarceration plays in producing structural racism. I think that it’s important to acknowledge that prison intellectual work is what provided the foundation for the abolitionist movement.

GD: You’ve asked about how it changed. I think it would be worth talking about the particular strategies that feminism have brought into the abolitionist movement that are much more prominent in its representation now and its practices now, and that’s some of what we try to track in the book. The way we conceptualize violence and the ways we conceptualize our own responsibilities in the world are very much driven by our feminism, which is rooted in Black feminism but very much developed in a context in which we’re asking questions about what leadership looks like, what fame looks like, what prominence looks like. How capitalism has to be thought through at the root of all of this. Those kinds of ways of thinking — intersectionality about feminist practice in an abolitionist context — are really what we try to underscore in the book.

We have now entered year three of the pandemic and for many people, the continued policy failure around the handling of Covid-19 has exposed the fault in all of our institutions. Most notably, prisons have become vectors for this disease and for the moral and political failure of this country. Have the past three years illuminated something new about the inherent harm of prisons?

GD: We often paraphrase Mandela: if you look inside a country’s prisons, you will see inside of the society. In many ways what we’re seeing through looking at Covid running through prisons and jails is just the exacerbation of the conditions that were already present. It’s made them more visible to some, but those conditions have been there all along. The healthcare for people inside, the potential to access all the things people need to thrive, are impossible inside of those conditions. Anyone who has been involved with prison abolition or in any ways involved in the system would understand the pandemic was going to be more difficult inside than it would be in the free world. It has forced some people to reckon with the very extreme nature of our tendency to assume that prisons and jails resolve our problems, and instead has allowed people to recognize those social problems will always be exacerbated, ostensibly, if we use prisons to handle them.

AD: I will only add that the strategy of decarceration that so many people supported, was in part followed but for the most part not followed as a response to the pandemic. Decarceration would have actually prevented the virus from raging in the way that it did in places like San Quentin, and prisons across the country. That was a moment that allows us to emphasize the various ways in which abolition turns out to be our most practical solution, and our most effective solution.

During the election season, you endorsed Biden and later expressed excitement about Kamala joining the ticket, which left many young abolitionists confused and even disappointed because the Biden-Harris ticket might be the most openly pro carceral ticket in recent memory. While the extensional threat of another Trump presidency was an understandable motivating force for many to go out and vote, your specific reasoning about being able to “push Biden to the left” came off as misguided. How do you feel now almost a year into Biden’s presidency?

AD: I never endorsed Biden. I argued that we had to evict fascism out of the White House. In all of the statements I made, I pointed out that Biden was certainly not the person we could expect to lead us in a progressive direction and I was very critical of Kamala Harris. I argued that we have to be very clear about why it might be necessary to cast a vote for Biden and Harris. That it was not a vote designed to represent them as even the best candidates that were available, but rather a vote designed to get rid of Trump and to get rid of fascism. And I’ve also pointed out over and over and over and over again, that I don’t think electoral politics are the best way to express radical politics and that the real change never comes from what elected officials do but rather from organized masses of people producing the radical effect in the course of our organizing. That’s how our world changes.

It is necessary for feminists to challenge themselves by thinking about abolition.

With the recent passing of bell hooks, I’m reminded of when you were on a Zoom call a few years ago Dr. Davis with Nikki Giovanni and how you all spoke about your friendship with the late author Toni Morrison. I’m also reminded of the story you’ve told about how Aretha Franklin once offered to bail you out of prison. Community is a tenet of abolition, so how has being in community with famous Black women artists whose work we’ve all come to know and love strengthened your beliefs in abolition?

AD: First of all, that community not only involves famous Black women. I think some of the most interesting ideas – and Toni would agree with this – come from people who haven’t achieved fame. With that having been said, I would argue that Toni Morrison has played such a transformative role in our world. Not only among Black women and Black people and not only people in the US but people all over the world. She demonstrated that it was possible to write about Black people and that everyone could be transformed by that.

And in that way, she encouraged us to engage in this process of radically transforming the way people think. Because abolition is not just about changing institutions, it’s about changing people’s ideas, it’s about changing prevailing ideology. And if anyone did that, she certainly did that. I miss her every day and I think about the ways in which she inspired so many people to change the world, in so many ways. We owe this current movement against racism to the work that she did in her own way.

GD: I was actually fortunate enough to meet both Toni and then Gloria, years before I met Angela actually. I think Toni needs to be remembered not only for her novels that many people know, but maybe most especially for all the publications that she enabled. There is an upcoming book about the work she did as an editor. I was fortunate enough to go to college and I met her while I was in college, but I also met her because she was editing many writers at that time that I also met. And her publications are really the foundation for Black studies in many ways. Not the publications that she wrote only, but the ones that she enabled.

She was also one of the first people who taught in those fields. I taught with her at Princeton in a class and that was my first job. In many ways, people don’t recognize how much that world of intellectuals and that world of powerful people laid a foundation beyond the books that have their names.

The thing about both bell hooks and Toni Morrison is they were always unafraid to who they were in the world. Toni would constantly assert herself in the very modality that Black women sometimes ran away from. She didn’t care if she was perceived as angry or difficult or anything else. She was really in adherence to her truth and that bell shared with her as well.

AD: We’ve lost so many people during this period. And bell hooks, who I met when we were both teaching together at San Francisco State many years ago before she became bell hooks – I still call her Gloria. And she decided she would use her talents as a writer to encourage people to be critical of the ideas that they had embodied as many of us do. Her death was a major blow to all of us.

A follow-up question: do the both of you consider yall selves to be artists and how has art helped push you as abolitionists? In the book, there’s the line “artists have always been key agents seeding resistance and providing tools for us to imagine otherwise.” Can you expand on that?

AD: I wish I were an artist [laughs]. Writing is an art.

GD: Some writing [also laughs].

AD: I get to learn from and appreciate art, literature, painting, film, music. I write. I’ve written about music. Both of us now are now involved in a collaborative book that addresses jazz without patriarchy. Art guides us. I have said many times that art helps us to feel what we do not yet understand, what we cannot yet say. So I’m a beneficiary of all the wonderful artists that helped pave the way to change and to reimagine the way we live and to imagine new worlds. All of us are beneficiaries of art, whether we produce art or not. And that’s one of the points we try to make in the book. We point out how cultural workers and artists have paved the way, and as a matter of fact we use graphics from many movement artists precisely in order to emphasize that point.

GD: I’m also not an artist, but art has been integral to the way I understand the world. It’s also been integral to the way I understood the role I play within the prison abolition movement. I’m now involved in a project called Visualizing Abolition which is based on working with artists and other culture producers, including musicians, to not only popularize anti-prison ideas but to imagine what the world without prisons would be like and is like. It is very difficult for us to imagine a world without prisons, considering the extent to which you’re surrounded by a popular culture that represents it as a permanent fixture.

In every Zoom session I’ve watched of yours, I always find myself peering behind you to look at your impressive book collection. What are some of those books on your shelf you find yourself returning to?

AD: A book like W.E.B Dubois Black Reconstruction in America. That informed our writing of Abolition.Feminism.Now. If you look at the book you’ll see numerous references to Dubois. We were talking about Toni Morrison. I always go back to her work. My friend the poet June Jordan, she’s a constant source of inspiration, especially since over the recent period many of us have become more involved in the struggle for Palestine and June was a pioneer in that respect. There is Stuart Hall. There is James Baldwin.

GD: Someone who comes up in the book a lot is Audre Lorde. Audre Lorde really helps to anchor the book because of the attention she had so early on to all the intimate and structural forces of violence and liberation. We always return to her. As someone who studied literature, I first learned about her as a poet. I love poetry and I love work in particular by people who use their poetry to communicate about this world in a transformative way.

I read hundreds of books about prison and a lot of them are very depressing and have a lot of information that is the same. That’s why we talk about people like Audre Lorde. It is important to read other kinds of things for us to stay inspired and to hold our imaginations in different ways. When we were writing the book, sometimes the four of us would be talking about poetry and other kinds of works that we love, because that’s a part of how we stay in the world doing this really difficult work. The activism that we document in this book is difficult. The daily care required to do all of the work that we know are engaged with every day takes a lot of work. People like Mariame Kaba, who are known now around the world, are especially important because they’re always inspiring by not only writing books but also sharing books, letting people know about books and making it possible for young people especially to imagine themselves in a world without prisons.

Last question: What brings you hope these days?

GD: The process of producing this book is really representative of what gives me hope. The collaboration that we had, which we wrote about as indicative of what it’s like to be in this movement, that inspires me. It inspires me to see, when I’m now teaching or speaking or working with groups, that people have already assimilated the language of abolition and have furthered it and have come to understand it. When you do this work, as an activist or even as a scholar, you don’t really get the world to take notice. You hope to leave something behind and you hope to benefit from having engaged with others in a way that makes your life meaningful. So we are very, very lucky to be living through this time which is full of great, great pain but also full of roots to ameliorate those painful things, in a way that wasn’t really on the table just a few years ago.

AD: I’m totally inspired by young activists because I don’t think I could ever imagine – even in my wildest imaginations – that we would be at this point. That there would be young people not only talking about feminism in an intersectional way, but embracing abolition. I’m so excited – I’m happy to be able to witness this. I never thought that I’d witness a moment like this.

Also let me say, I’m excited about this book Abolition.Feminsm.Now. and the way we produced it. Intellectuals usually work under solitary conditions and we wrote this book together; we really wrote this book together. It does not represent us individually, it represents us collectively. We created a different voice that is more than just our four voices. At first, we didn’t know we’d be able to do this, because doing this kind of collaborative work is very, very difficult. But if it’s possible in the writing of this book, it’s possible in many other contexts too.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Original Article posted on Harpers Bazaar.